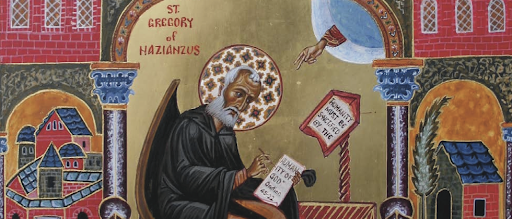

St. Gregory Nazianzen

St. Gregory Nazianzen, B.C., Doctor of the Church

From his own works, and other monuments of that age. See Gregory of Caesarea, who writ his life in 940; Hermant, Tillemont, t. ix., Ceillier, t. vii.; also the life of this saint, compiled from his works by Baronius, published by Alberici, in an appendix to the life and letters of that cardinal, in 1759, t. ii.]

St Gregory who, from his profound skill in sacred learning, is surnamed the Theologian, was a native of Arianzum, an obscure village in the territory of Nazianzum, a small town in Cappadocia not far from Caesarea His parents are both honoured in the calendars of the church: his father on the 1st of January and his mother Nonna on the 5th of August. She drew down the blessing of heaven upon her family by most bountiful and continual alms-deeds, in which she knew one of the greatest advantages of riches to consist; yet, to satisfy the obligation of justice which she owed to her children, she by her prudent economy improved at the same time their patrimony. The greatest part of her time she devoted to holy prayer; and her respect and attention to the least thing which regarded religion is not to be expressed. His father, whose name also was Gregory, was from his infancy a worshipper of false gods, but of the sect called the Hipsistarii, on account of the profession they made of adoring the Most High God. The prayers and tears of Nonna at length obtained of God the conversion of her husband, whose integrity in the discharge of the chief magistracy of his town and the practice of strict moral virtue prepared him for such a change. His son has left us the most edifying detail of his humility, holy zeal, and other virtues.[1] He had three children, Gorgonia, Gregory, and Caesarius, who was the youngest. Gregory was the fruit of the most earnest prayers of his mother who, upon his birth, offered him to God for the service of his church. His virtuous parents gave him the strongest impressions of piety in his tender age; and his chief study, from his very infancy, was to know God by the help of pious books, in the reading whereof he was very assiduous.

Having acquired grammar-learning in the schools of his own country, and being formed to piety by domestic examples, he was sent to Caesarea, in Palestine, where the study of eloquence flourished. He pursued the same studies some time at Alexandria, and there embarked for Athens in November. The vessel was beaten by a furious storm during twenty days, without any hopes either for the ship or passengers; all which time he lay upon the deck, bemoaning the danger of his soul on account of his not having been as yet baptized, imploring the divine mercy with many tears and loud groans, and frequently renewing his promise of devoting himself entirely to God in case he survived the danger. God was pleased to hear his prayer: the tempest ceased and the vessel arrived safe at Rhodes, and soon after at Aegina, an island near Athens. He had passed through Caesarea of Cappadocia in his road to Palestine; and making some stay there to improve himself under the great masters of that city, had contracted an acquaintance with the great St. Basil, which he cultivated at Athens, whither that saint followed him soon after. The intimacy between these two saints became from that time the most perfect model of holy friendship, and nothing can be more tender than the epitaph which St. Gregory composed upon his friend. Whilst they pursued their studies together, they shunned the company of those scholars who sought too much after liberty, and conversed only with the diligent and virtuous. They avoided all feasting and vain entertainments; and were acquainted only with two streets, one that led to the church and the other to the schools. Riches they despised and accounted as thorns, employing their allowance in supplying themselves with bare necessaries for an abstemious and slender subsistence, and disposing of the remainder in behalf of the poor. Envy had no place in them; sincere love made each of them esteem his companion’s honour and advantage as his own; they were to each other a mutual spur to all good, and by a holy emulation neither of them would be outdone by the other in fasting, prayer, or the exercise of any virtue. Saint Basil left Athens first. The progress which St. Gregory made here in eloquence, philosophy, and the sacred studies appears by the high reputation which he acquired, and by the monuments which he has left behind him. But his greatest happiness and praise was, that he always made the love and fear of God his principal affair, to which he referred his studies and all his endeavours. In 355 Julian, afterwards emperor, came to Athens, where he spent some months with St. Basil and St. Gregory in the study of profane literature and the holy scriptures. St. Gregory then prognosticated what a mischief the empire was breeding up in that monster—from the levity of his carriage, the rolling and wandering of his eyes, the fierceness of his looks, the tossing of his head, the shrugging up of his shoulders, his uneven gait, his loud and unseasonable laughter, his rash and incoherent discourse—the indications of an unsettled and arrogant mind.[2] The year following, our saint left Athens for Nazianzum and took Constantinople in his way. Here he found his brother Gesarius arrived not long before from Alexandria, where he had accomplished himself in all the polite learning of that age and applied himself particularly to physic. The Emperor Constantius honoured him with his favour and made him his chief physician. His generosity appeared I in this station by his practice of physic, even among the rich, without the inducement of either fee or reward. He was also a father to the poor, on whom he bestowed the greatest part of his income. Gregory was importuned by many to make his appearance at the bar, or at least to teach rhetoric, as that which would afford him the best means to display talents and raise his fortune in the world. But he answered that he totally devoted himself to the service of God.

The first thing he did after his return to Nazianzum was to fulfil his engagement of consecrating himself entirely to God by receiving baptism at the hands of his father. This he did without reserve: “I have,” says he,[3] “given all I have to him from whom I received it, and have taken him alone for my whole possession. I have consecrated to him my goods, my glory, my health, my tongue, and talents. All the fruit I have received from these advantages has been the happiness of despising them for Christ’s sake.” From that moment never was man more dead to ambition, riches, pleasures, or reputation. He entertained no secret affection for the things of this world, but trampled under his feet all its pride and perishable goods; finding no ardour, no relish, no pleasure but in God and in heavenly things. His diet was coarse bread, with salt and water.[4] He lay upon the ground; wore nothing but what was coarse and vile. He worked hard all day, spent a considerable part of the night in singing the praises of God, or in contemplation.[5] With riches he contemned also profane eloquence, on which he had bestowed so much pains, making an entire sacrifice of it to Jesus Christ. His classics and books of profane oratory he abandoned to the worms and moths.[6] He regarded the greatest honours as vain dreams, which only deceive men, and dreaded the precipices down which ambition drags its inconsiderate slaves. Nothing appeared to him comparable to the life which a man leads who is dead to himself and his sensual inclinations; who lives as it were out of the world, and has no other conversation but with God.[7] However, he for some time took upon him the care of his father’s household and the management of his affairs. He was afflicted with several sharp fits of sickness, caused by his extreme austerities and continual tears, which often did not suffer him to sleep.[8] He rejoiced in his distempers, because in them he found the best opportunities of mortification and self-denial.[9] The immoderate laughter, which his cheerful disposition had made him subject to in his youth, was afterwards the subject of his tears. He obtained so complete a conquest over the passion of anger as to prevent all indeliberate motions of it, and became totally indifferent in regard to all that before was most dear to him. His generous liberality to the poor made him always as destitute of earthly goods as the poorest, and his estate was common to all who were in necessity, as a port is to all at sea.[10] Never does there seem to have been a greater lover of retirement and silence. He laments the excesses into which talkativeness draws men, and the miserable itch that prevails in most people to become teachers of others.[11]

It was his most earnest desire to disengage himself from the converse of men and the world, that he might more freely enjoy that of heaven. He accordingly, in 358, joined St. Basil in the solitude into which he had retreated, situate near the river Iris, in Pontus. Here, watching, fasting, prayer, studying the holy scriptures, singing psalms, and manual labour employed their whole time. As to their exposition of the divine oracles, they were guided in this not by their own lights and particular way of thinking, but, as Rufinus writes,[12] by the interpretation which the ancient fathers and doctors of the church had delivered concerning them. But this solitude Gregory enjoyed only just long enough to be enamoured of its sweetness, being soon recalled back by his father, then above eighty, to assist him in the government of his flock. To draw the greater succour from him he ordained him priest by force and when he least expected it. This was performed in the church on some great festival, and probably on Christmas Day in 361. He knew the sentiments of his son with regard to that charge, and his invincible reluctance on several accounts, which was the reason of his taking this method. The saint accordingly speaks of his ordination as a kind of tyranny which he knew not well how to digest; in which sentiments he flew into the deserts of Pontus and sought relief in the company of his dear friend St. Basil, by whom he had been lately importuned to return. Many censured this his flight, ascribing it to pride, obstinacy, and the like motives. Gregory likewise, himself, reflecting at leisure on his own conduct and the punishment of the prophet Jonas for disobeying the command of God, came to a resolution to go back to Nazianzum; where, after a ten weeks’ absence, he appeared again on Easter Day, and there preached his first sermon on that great festival. This was soon after followed by another, which is extant, under the title of his apology for his flight.

In this discourse St. Gregory extols the unanimity of that church in faith and their mutual concord; but towards the end of the reign of Julian, an unfortunate division happened in it, which is mentioned by the saint in his first invective against that apostate prince.[13] The bishop, his father, hoping to gain certain persons to the church by condescension, admitted certain writing which had been drawn up by the secret favourers of Arianism in ambiguous and artful terms. This unwary condescension of the elder Gregory gave offence to the more zealous part of his flock, and especially to the monks, who refused thereupon to communicate with him. Our saint discharged his duty so well in this critical affair that he united the flock with their pastor without the least concession in favour of the error of those by whom his father had been tricked into a subscription against his intention and design, his faith being entirely pure. On the occasion of this joyful reunion our saint pronounced an elegant discourse.[14] Soon after the death of Julian he composed his two invective orations against that apostate. He imitates the severity which the prophets frequently made use of in their censure of wicked kings; but his design was to defend the church against the pagans by unmasking the injustice, impiety, and hypocrisy of its capital persecutor. The saint’s younger brother, Caesarius, had lived in the court of Julian, highly honoured by that emperor for his learning and skill in physic. St. Gregory pressed him to forsake the family of an apostate prince, in which he could not live without being betrayed into many temptations and snares.[15] And so it happened; for Julian, after many caresses, assailed him by inveigling speeches, and at length, by a warm disputation in favour of idolatry. Caesarius answered him that he was a Christian, and such he was resolved always to remain. However, apprehensive of the dangers in which he lived, he soon after chose rather to resign his post than to run the hazard of his faith and a good conscience. He therefore left the court, though the emperor endeavoured earnestly to detain him. After the miserable death of the apostate, he appeared again with distinction in the courts of Jovian and Valens, and was made by the latter , or treasurer of the imperial rents, which office was but a step to higher dignities. In the discharge of this employment of Bithynia he happened to be at Nice in the great earthquake, which swallowed up the chief part of that city in 360. The treasurer, with some few others, escaped by being preserved through a wonderful providence in certain hollow parts of the ruins. St. Gregory improved this opportunity to urge him again to quit the world and its honours, and to consecrate to God alone a life for which he was indebted to him on so many accounts.[16] Gesarius, moved by so awakening an accident, listened to his advice and took a resolution to renounce the world; but returning home, fell sick and died in the fervour of his sacrifice, about the beginning of the year 368, leaving his whole estate to the poor.[17] He is named in the Roman Martyrology on the 25th of February. St. Gregory, extolling his virtue, says that whilst he enjoyed the honours of the world he looked upon the advantage of being a Christian as the first of his dignities and the most glorious of all his titles, reckoning all the rest dross and dung. He was buried at Nazianzum, and our saint pronounced his funeral panegyric, as he also did that of his holy sister Gorgonia, who died soon after. He extols her humility; her prayer often continued whole nights with tears; her modesty, prudence, patience, resignation, zeal, respect for the ministers of God and for holy places; her liberality to them and great charity to the poor; her penance, extraordinary care of the education of her children, &c. He mentions as miraculous her being cured of a palsy by praying at the foot of the altar, and her recovery after great wounds and bruises which she had received by a fall from her chariot.

In 372 Cappadocia was divided by the emperor into two provinces, and Tyana made the capital of that which was called the second. Anthimus, bishop of that city, pretended hence to an archiepiscopal jurisdiction over the second Cappadocia. St. Basil, the Metropolitan of Cappadocia, maintained that the civil division of the province had not infringed his jurisdiction, though he afterwards, for the sake of peace, yielded the second Cappadocia to the see of Tyana. He appointed our saint Bishop of Sasima, a small town in that division. Gregory stood out a long time, but at length submitted, overcome by the authority of his father and the influence of his friend. He accordingly received the episcopal consecration from the hands of St. Basil, at Caesarea, about the middle of the year 372. But he repaired to Nazianzum to wait a favourable opportunity of taking possession of his church of Sasima, which never happened; for Anthimus, who had in his interest the new governor, and was master of all the avenues and roads to that town, would by no means admit him. Basil reproached his friend with sloth; but St. Gregory answered him that he was not disposed to fight for a church.[18] He, however, charged himself with the government of that of Nazianzum under his father till his death, which happened the year following. St. Gregory pronounced his funeral panegyric in presence of St. Basil and of his mother, St. Nonna, who died shortly after. Holy solitude had been the constant object of his most earnest desires, and he had only waited the death of his father entirely to bury himself in it. Nevertheless, yielding to the importunities of others and to the necessities of the church of Nazianzum, he consented to continue his care of it till the neighbouring bishops could provide it with a pastor. But seeing this affair protracted, and finding himself afflicted with various distempers, he left that city and withdrew to Seleucia, the metropolis of Isauria, in 375, where he continued five years. The death of St. Basil, in 379, was to him a sensible affliction, and he then composed twelve epigrams or epitaphs to his memory; and some years after pronounced his panegyric at Caesarea, namely, in 381 or 382. The unhappy death of the persecuting emperor Valens, in 378, restored peace to the church. The Catholic pastors sought means to make up the breaches which heresy had made in many places. For this end they held several assemblies and sent zealous and learned men into the provinces in which the tyrant had made the greatest havoc. The church of Constantinople was of all others in the most desolate and abandoned condition, having groaned during forty years under the tyranny of the Arians, and the few Catholics who remained there having been long without a pastor and even without a church wherein to assemble. They, being well acquainted with our saint’s merit, importuned him to come to their assistance, and were backed by several bishops, desirous that his learning, eloquence, and piety might restore that church to its splendour. But such were the pleasures he enjoyed in his beloved retirement at Seleucia, and in his thorough disengagement from the world, that for some time these united solicitations made little or no impression on him. They had, however, at length their desired effect. His body bent with age, his head bald, his countenance extenuated with tears and austerities, his poor garb, and his extreme poverty made but a mean appearance at Constantinople; and no wonder that he was at first ill received in that polite and proud city. The Arians pursued him with calumnies, raillieries, and insults. The prefects and governors added their persecutions to the fury of the populace, all which concurred to acquire him the glorious title of confessor. He lodged first in the house of certain relations, where the Catholics first assembled to hear him. He soon after converted it into a church and gave it the name of Anastasia, or the Resurrection, because the Catholic faith, which in that city had been hitherto oppressed, here seemed to be raised, as it were, from the dead. Sozomen relates that this name was confirmed to it by a miraculous raising to life of a woman then with child, who was killed by falling from a gallery in it, but returned to life by the prayers of the congregation.[19] Another circumstance afterwards confirmed in this church the same name. During the reign of the Emperor Leo the Thracian, about the year 460, the body of St. Anastasia, virgin and martyr, was brought from Sirmich to Constantinople and laid in this place, as is recorded by Theodorus the Reader.[20] But this church is not to be confounded with another of the same name, which was in the hands of the Novatians under Constantius and Julian the Apostate.[21]

In this small church Nazianzen preached, and every day assembled his little flock, which increased daily. The Arians and Apollinarists, joined with other sects, not content to defame and calumniate him, had recourse to violence on his person. They pelted him with stones as he went along the streets, and dragged him before the civil magistrates as a malefactor, charging him with tumult and sedition. But he comforted himself on reflecting that though they were the stronger party he had the better cause; though they possessed the churches, God was with him; if they had the populace on their side, the angels were on his, to guard him. St. Jerome coming out of the deserts of Syria to Constantinople became the disciple and scholar of St. Gregory, and one of those who studied the holy scripture under him, of which that great doctor glories in his writings. Our holy pastor, being a lover of solitude, seldom went abroad or made any visits, except such as were indispensable; and the time that was not employed in the discharge of his functions he devoted to prayer and meditation, spending a considerable part of the night in those holy exercises. His diet was herbs and a little salt with bread. His cheeks were furrowed with the tears which he shed, and he daily prostrated himself before God to implore his light and mercy upon his people. His profound learning, his faculty of forming the most noble conceptions of things, and the admirable perspicuity, elegance, and propriety with which he explained them, charmed all who heard him. The Catholics flocked to his discourses as men parching with thirst eagerly go to the spring to quench it. Heretics and pagans resorted to them, admiring his erudition and charmed with his eloquence. The fruits of his sermons were every day sensible; his flock became in a short time very numerous, and he purged the people of that poison which had corrupted their hearts for many years. St. Gregory heard, with blushing and confusion, the applause and acclamations with which his discourses were received; and his fear of this danger made him speak in public with a certain timidity and reluctance. He scorned to flatter the great ones, and directed his discourses to explain and corroborate the Catholic faith and reform the manners of the people. He taught them that the way to salvation was not to be ever disputing about matters of religion (an abuse that was grown to a great height at that time in Constantinople), but to keep the commandments,[22] to give alms, to exercise hospitality, to visit and serve the sick, to pray, sigh, and weep; to mortify the senses, repress anger, watch over the tongue, and subject the body to the spirit. The envy of the devil and of his instruments could not bear the success of his labours, and by exciting trouble found means to interrupt them. Maximus, a native of Alexandria, a cynic philosopher, but withal a Christian, full of the impudence and pride of that sect, came to Constantinople; and under an hypocritical exterior disguised a heart full of envy, ambition, covetousness, and gluttony. He imposed on several, and for some time on St. Gregory himself, who pronounced an enlogium of this man in 379, now extant, under the title of the Eulogium of the Philosopher Hero; but St. Jerome assures us that instead of Hero we ought to read Maximus. This wolf in sheep’s clothing having gained one of the priests of the city, and some partizans among the laity, procured himself to be ordained Bishop of Constantinople in a clandestine manner, by certain Egyptian bishops who lately arrived on that intent. The irregularity of this proceeding stirred up all the world against the usurper. Pope Damasus writ to testify his affliction on that occasion, and called the election null. The Emperor Theodosius the Great, then at Thessalonica, rejected Maximus with indignation; and coming to Constantinople, proposed to Demophilus, the Arian bishop, either to receive the Nicene faith or to leave the city; and upon his preferring the latter, his majesty, embracing St. Gregory, assured him that the Catholics of Constantinople demanded him for their bishop, and that their choice was most agreeable to his own desires. Theodosius, within a few days after his arrival, drove the Arians out of all the churches in the city and put the saint in possession of the Church of St. Sophia, upon which all the other churches of the city depended. Here the clamours of the people were so vehement that Gregory might be their bishop that all was in confusion till the saint prevailed upon them to drop that subject and to join in praise and thanksgiving to the ever blessed Trinity for restoring among them the profession of the true faith. The emperor highly commended the modesty of the saint. But a council was necessary to declare the see vacant and the promotion of the Arian Demophilus and of the cynic Maximus void and null. A synod of all the East was then meeting at Constantinople, in which St. Meletius, Patriarch of Antioch, presided. He being the great friend and admirer of Nazianzen, the council took his cause into consideration before all others, declared the election of Maximus null, and established St. Gregory Bishop of Constantinople, without having any regard to his tears and expostulations. St. Meletius dying during the synod, St. Gregory presided in the latter sessions. To put an end to the schism between Meletius and Paulinus at Antioch, it had been agreed that the survivor should remain in sole possession of that see. This Nazianzen urged; but the oriental bishops were unwilling to own for patriarch one whom they had opposed. They therefore took great offence at this most just and prudent remonstrance, and entered into a conspiracy with his enemies against him. The saint, who had only consented to his election through the importunity of others, was most ready to relinquish his new dignity. This his enemies sought to deprive him of, together with his life, on which they made several attempts. Once, in particular, they hired a ruffian to assassinate him. But the villain, touched with remorse, repaired to the saint with many tears, wringing his hands, beating his breast, and confessing his black attempt, which he should have put in execution had not Providence interposed. The good bishop replied: “May God forgive you; his gracious preservation obliges me freely to pardon you. Your attempt has now made you mine. One only thing I beg of you, that you forsake your heresy and sincerely give yourself to God.” Some warm Catholics complained of his lenity and indulgence towards the Arians, especially those who had shown themselves violent persecutors under the former reigns.

In the meantime the bishops of Egypt and those of Macedonia arriving at the council, though all equally in the interest of Paulinus of Antioch, complained that Gregory’s election was uncanonical, it being forbidden by the canons to transfer bishops from one see to another. Nazianzen calmly answered that those canons had lost their force by long disuse: which was most notorious in the East. Nor did they in the least regard his case; for he had never taken possession of the see of Sasima, and only governed that of Nazianzum as vicar under his father. However, seeing a great ferment among the prelates and people, he cried out in the assembly, “If my holding the see of Constantinople gives any disturbance, behold I am very willing, like Jonas, to be cast into the sea to appease the storm, though I did not raise it. If all followed my example, the church would enjoy an uninterrupted tranquillity. This dignity I never desired; I took this charge upon me much against my will. If you think fit, I am most ready to depart; and I will return back to my little cottage, that you may remain here quiet, and the church of God enjoy peace. I only desire that the see may be filled by a person that is capable and willing to defend the faith.”[23] He thereupon left the assembly, overjoyed that he had broken his bands. The bishops, whom he left in surprise, but too readily accepted his resignation. The saint went from the council to the palace, and falling on his knees before the emperor and kissing his hand, said, “I am come, sir, to ask neither riches nor honours for myself or friends, nor ornaments for the churches, but licence to retire. Your majesty knows how much against my will I was placed in this chair. I displease even my friends on no other account than because I value nothing but God. I beseech you, and make this my last petition, that among your trophies and triumphs you make this the greatest, that you bring the church to unity and concord.” The emperor and those about him were astonished at such a greatness of soul, and he with much difficulty was prevailed on to give his assent. This being obtained, the saint had no more to do than to take his leave of the whole city, which he did in a pathetic discourse, delivered in the metropolitan church before the hundred and fifty fathers of the council and an incredible multitude of the people.[24] He describes the condition in which he had found that church on his first coming to it and that in which he left it, and gives to God his thanks and the honour of the re-establishment of the Catholic faith in that city. He makes a solemn protestation of the disinterestedness of his own conduct during his late administration, not having touched any part of the revenues of the see of Constantinople the whole time. He reproaches the city with the love of shows, luxury, and magnificence, and says he was accused of too great mildness, also of a meanness of spirit, from the lowly appearance he made with respect both to dress and table. He vindicates his behaviour in these regards, saying, “I did not take it to be any part of my duty to vie with consuls, generals, and governors, who know not how to employ their riches otherwise than in pomp and show. Neither did I imagine that the necessary subsistence of the poor was to be applied to the support of luxury, good cheer, a prancing horse, a sumptuous chariot, and a long train of attendants. If I have acted in another manner and have thereby given offence, the fault is already committed and cannot be recalled, but I hope is not unpardonable.” He concludes by bidding a moving farewell to his church, to his dear Anastasia, which he calls, in the. language of St. Paul, his glory and his crown; to the cathedral and all the other parishes of the city, to the holy apostles as honoured in the magnificent church (in which Constantius had placed the relics of St. Andrew, St. Luke, and St. Timothy), to the episcopal throne, to the clergy, to the holy monks and the other pious servants of God, to the emperor and all the court with its jealousies, pomp, and ambition, to the East and West divided in his cause, to the tutelar angels of his church, and to the sacred Trinity honoured in that place. He concludes with these words: “My dear children, preserve the depositum of faith, and remember the stones which have been thrown at me because I planted it in your hearts.” The saint was most tenderly affected in abandoning his dear flock—his converts especially which he had gained at his first church of Anastasia, as they had already signalized themselves in his service by suffering persecutions with patience for his sake. They followed him weeping, and entreating him to abide with them. He was not insensible to their tears; but motives of greater weight obliged him not to regard them on this occasion. St. Gregory, seeing himself at liberty, rejoiced in his happiness, as he expressed himself some time after to a friend in these words: “What advantages have not I found in the jealousy of my enemies! They have delivered me from the fire of Sodom by drawing me from the dangers of the episcopal charge.”[25] This treatment was the recompense with which men rewarded the labours and merit of a saint whom they ought to have sought in the remotest corners of the earth: but that city was not worthy to possess so great and holy a pastor. He had in that short time brought over the chief part of its inhabitants to the Catholic faith, as appears from his works and from St. Ambrose.[26] He had conquered the obstinacy of heretics by meekness and patience, and thought it a sufficient revenge for their former persecutions that he had it in his power to chastise them.[27] The Catholics he induced to show the same moderation towards them, and exhorted them to serve Jesus Christ by taking a Christian revenge of them, the bearing their persecutions with patience and the overcoming evil with good.[28] Besides establishing the purity of faith, he had begun a happy reformation of manners among the people; and much greater fruits were to be expected from his zealous labours. Nectarius, who succeeded him, was a soft man, and by no means equal to such a charge.

Before the election of Nectarius, Gregory left the city and returned to Nazianzum. In that retirement he composed the poem on his own life, particularly dwelling on what he had done at Constantinople to obviate the scandalous slanders which were published against him. He laboured to place a bishop at Nazianzum, but was hindered by the opposition of many of the clergy. Sickness obliged him to withdraw soon after to Arianzum, probably before the end of the year 381. In his solitude he testifies[29] that he regretted the absence of his friends, though he seemed insensible to everything else of this world. To punish himself for superfluous words (though he had never spoken to the disparagement of any neighbour) he, in 382, passed the forty days of Lent in absolute silence. In his desert he never refused spiritual advice to any that resorted to him for it. In his parzenetic poem to St. Olympias he lays down excellent rules for the conduct of married women. Among other precepts, he says, “In the first place, honour God; then respect your husband as the eye of your life, for he is to direct your conduct and actions. Love only him; make him your joy and your comfort. Take care never to give him any occasion of offence or disgust. Yield to him in his anger; comfort and assist him in his pains and afflictions, speaking to him with sweetness and tenderness, and making him prudent and modest remonstrances at seasonable times. It is not by violence and strength that the keepers of lions endeavour to tame them when they see them enraged; but they soothe and caress them, stroking them gently, and speaking with a soft voice. Never let his weaknesses be the subject of your reproaches. It can never be just or allowable for you to treat a person in this manner whom you ought to prefer to the whole world.” He prays that this holy woman might become the mother of many children, that there might be the more souls to sing the praises of Jesus Christ.[30] He often repeats this important advice, that everyone begin and end every action by offering his heart and whatever he does to God by a short prayer.[31] For we owe to God all that we are or have; and he accepts and rewards the smallest action, not so much with a view to its importance as to the affection of the heart, which in his poverty gives what it has, and is able to give in return for God’s benefits and in acknowledgment of his sovereignty.

St. Gregory had been obliged to govern the vacant see of Nazianzum after the death of his father, leaving the chief care of that church to Cledonius in his absence. But in 382 he procured Eulalias to be ordained bishop of that city, and spent the remainder of his life in retirement near Arianzum, still continuing to aid that church with his advice, though at that time very old and infirm. In this private abode he had a garden, a fountain, and a shady grove, in which he took much delight. Here, in company with certain solitaries, he lived estranged from pleasures and in the practice of bodily mortification, fasting, watching, and praying much on his knees. “I live,” says he, “among rocks and with wild beasts, never seeing any fire or using shoes; having only one single garment.[32] I am the outcast and the scorn of men. I lie on straw, clad in sackcloth: my floor is always moist with the tears I shed.”[33] In the decline of life he set himself to write pious poems for the edification of such among the faithful as were fond of music and poetry. He had also mind to oppose the poems made use of by the Apollinarist heretics to propagate their errors by such as were orthodox, useful, and religious, as the priest Gregory says in his life. He considered this exercise also as a work of penance, compositions in metre being always more difficult than those in prose. He therein recounts the history of his life and sufferings: he publishes his faults, his weaknesses, and his temptations, enlarging much more on these than on his great actions. He complains of the annoyance of his rebellious flesh, notwithstanding his great age, his ill state of health, and his austerities, acknowledging himself wholly indebted to the divine grace which had always preserved in him the treasure of virginity inviolable. God suffered him to feel these temptations that he might not be exposed to the snares of vanity and pride; and that whilst his soul dwelt in heaven he might be put in mind by the rebellion of the body that he was still on earth in a state of war. His poems are full of cries of ardent love, by which he conjures Jesus Christ to assist him, without whose grace he declares we are only dead carcasses, exhaling the stench of sin, and as incapable of making one step as a bird is of flying without air, or a fish of swimming without water; for he alone makes us see, act, and run.[34] He joined great watchfulness to prayer, especially shunning the conversation and neighbourhood of women,[35] over and above the assiduous maceration of his body. In his letters he gives to others the same advice, of which his own life was a constant example. One instance shall suffice. Sacerdos, a holy priest, was fallen into an unjust persecution through slander. St. Gregory writes to him thus in his third letter: “What evil can happen to us after all this? None, certainly, unless we by our own fault lose God and virtue. Let all other things fall out as it shall please God. He is the master of our life, and knows the reason of everything that befalls us. Let us only fear to do anything unworthy our piety. We have fed the poor, we have served our brethren, we have sung the psalms with cheerfulness. If we are no longer permitted to continue this, let us employ our devotion some other way. Grace is not barren, and opens different ways to heaven. Let us live in retirement; let us occupy ourselves in contemplation; let us purify our souls by the light of God. This perhaps will be no less a sacrifice than anything we can do.” These were St. Gregory’s occupation from the time of his last retirement till his happy death in 389, or, according to others, in 391. Tillemont gives him only sixty or sixty-one years of age, but he was certainly considerably older. The Latins honour him on the 8th of May. The Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus caused his ashes to be translated from Nazianzum to Constantinople, and to be laid in the Church of the Apostles, which was done with great pomp in 950. They were brought to Rome in the crusades and lie under an altar in the Vatican Church.

This great saint looked upon the smiles and frowns of the world with indifference, because spiritual and heavenly goods wholly engrossed his soul. “Let us never esteem worldly prosperity or adversity as things real or of any moment,” said he,[36] “but let us live elsewhere, and raise all our attention to heaven, esteeming sin as the only true evil, and nothing truly good but virtue, which unites us to God.”